What Was the Focus of Protests by the Art Workersã¢â⢠Coalition in 1969?

Antiwar march October 31, 1970, Seattle, ii months subsequently the death of Reuben Salazar in the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium protest

Antiwar march October 31, 1970, Seattle, ii months subsequently the death of Reuben Salazar in the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium protest by Josue Estrada

The Chicano movement that took shape in the late 1960s transformed the identity, the politics, and the community dynamics of Mexican Americans. The movement had many dimensions and no single organization could represent the full range of agendas, objectives, tactics, approaches, and ideologies that activists pursued. The largest and well-nigh notable organizations included the United Farm Workers Union, the Alianza Federal del Pueblos Libres, the Crusade for Justice, and the Raza Unida Party (formerly the Mexican American Youth Organization).

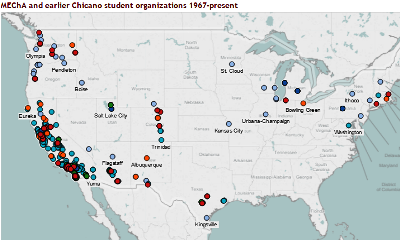

Key to the Chicano movement were as well student and youth organizations such as the Brown Berets and the United Mexican American Students, the Mexican American Student Confederation, and the Mexican American Student Association that eventually merged to form El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano/a de Aztlan (MEChA) in 1969.

The use of term Chicano rather than Mexican American in the title of the organisation was intentional. Chicano signaled a rejection of a Mexican American identity that accepted assimilation and shunned their cultural roots. Instead, MEChistA's opted to identify equally Chicanos, reflecting their commitment to a new political consciousness, self-respect, and pride in their cultural background.

Scholars accept paid some attention to the geography of Chicano activism but not in the detail that at present becomes possible with the maps this project provides. The starting assumption is that the movement was concentrated in the Southwest where Mexican American populations were largest. That is true but our maps show activism was not spread evenly through the region and that sure organizations and types of activism were limited to particular geographies. [The accompanying images will have you to large-format interactive maps that show twelvemonth-by-year or month-past-month the changing geography of 8 organizations]

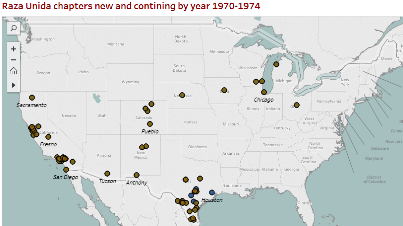

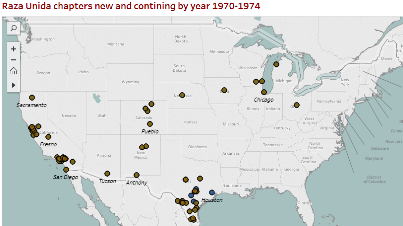

Click to see twelvemonth-by-yr interactive Raza Unida maps

For instance, in southern Texas where Mexican Americans comprised a significant portion of the population and had a history of electoral participation, the Raza Unida Party started in 1970 by Jose Angel Gutierrez hoped to win elections and mobilize the voting ability of Chicanos. RUP thus became the focus of considerable Chicano activism in Texas in the early 1970s.

The motility in California took a different shape, less concerned well-nigh elections. Chicanos in Los Angeles formed alliances with other oppressed people who identified with the Third Earth Left and were committed to toppling U.S. imperialism and fighting racism. The Dark-brown Berets, with links to the Blackness Panther Political party, was one manifestation of the multiracial context in Los Angeles. The Chicano Moratorium antiwar protests of 1970 and 1971 too reflected the vibrant collaboration between African Americans, Japanese Americans, American Indians, and white antiwar activists that had developed in Southern California.

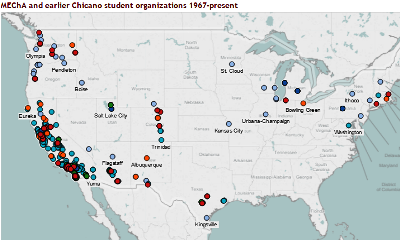

Click to see year-past-year interactive maps of MEChA chapters 1969-2012

Chicano student activism likewise followed particular geographies. MEChA established in Santa Barbara, California in 1969, united many academy and college Mexican American groups nether one umbrella organization. MEChA became a multi-state system, but an examination of the year-by-twelvemonth expansion shows a connected concentration in California. Our maps and charts demonstrate that as the organisation added dozens then hundreds of chapters, the vast majority were in California, which should atomic number 82 scholars to ask what atmospheric condition fabricated the state unique, and to wonder why Chicano students in other states were less interested in organizing MEChA chapters.

In the essay that follows, I will briefly appraise the geography of Mexican American activism beginning with organizations founded before the Chicano era of the 1960 and 1970s.

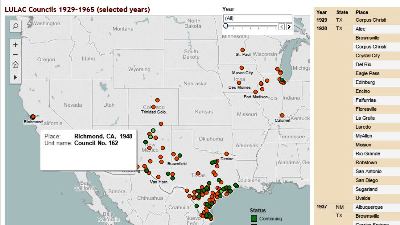

Mexican American Activism 1929-1967

The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was the most important Mexican American civil rights organization for much of the 20th century. Founded in 1929, in Corpus Christi, Texas, it was modeled after the NAACP and was largely the creation of activist Tejanos. The organization expanded quickly throughout south Texas but it was not until the mid-1930s that a chapter appeared outside of Texas and just in the mid-1940s did Mexican Americans in California begin to form chapters. In the late 1950s and early 1960s chapters formed in Chicago and other Midwestern cities.

Click to run into year-by-yr interactive maps of LULAC councils 1929-1977

LULAC'south founders were professionals and merchants committed to working within the American political and economic organization. The organization assisted Mexican Americans acquire voting rights and greater equality especially in employment and education. One of LULAC's notable achievements was their financial support for a successful federal lawsuit (Méndez five. Westminster) which argued that segregation of Mexican Americans in the public schools of Orange County, California, was unlawful. The 1947 appellate court ruling became a precursor to Brownish v. Lath Supreme Court ruling that declared schoolhouse segregation unconstitutional nationwide in 1954. Curiously, LULAC'south arguments for equal access in schools and employment rested on the notion that Mexican Americans were legally white and therefore deserved equal rights akin to white Americans. This was the kind of cautious position that the activists of the Chicano generation would later on criticize or condemn. Cynthia E. Orozco's No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement (2009), explains that LULAC members in 1920s and 1930s did resist European American domination simply used strategies commensurate to the era's focus on absorption and anti-immigrant sentiment.

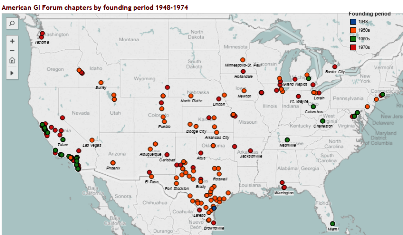

Taking a similar approach to LULAC, the American GI Forum was established in 1948 to accost the discrimination experienced by returning World State of war 2 Mexican American GI's in the areas of employment, medical attention, housing, and teaching. These problems were peculiarly widespread in Texas where Dr. Hector P. Garcia and attorney Gustavo Garcia started the organization. The master objectives of the GI Forum were to aid needy and disabled veterans through irenic and autonomous means. The GI Forum since its inception expressed a strong patriotic sentiment toward the United states, swore to protect the constitution, and defend the nation from all enemies.

Click to see year-past-twelvemonth interactive maps of GI Forum chapters 1948-1974

Shortly afterwards its founding, the GI Forum became a key institution that galvanized land and national attention when a white-owned mortuary refused to bury a Mexicano war veteran, Private Felix Longoria, in the white cemetery. Garcia was able to secure Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson'southward back up and Private Longoria was cached in 1949 at Virginia'due south Arlington National Cemetery. The so-called "Longoria affair" was a goad for the expansion of the American GI Forum across Texas.

Similar LULAC, the GI Forum rooted itself in Texas and spread slowly to other states. Information technology was not until the 1960s that the arrangement became popular in California, and councils were founded in the Midwest and along the E coast in Connecticut, Maryland and Washington D.C. In contrast to LULAC, the America GI Forum was more willing to engage in oppositional politics and some of its members wearing their caps marched in solidarity with Chicanos protestors. Betwixt 1969 and 1979, the Forum led a national boycott against the Adolph Coors Company, 1 of the largest beer producers in the nation, challenging the corporation'southward discriminatory employment practices affecting Chicanos. The American GI Forum, withal, never formally supported the radical political activism of the Chicano motility.

United Farm Workers Union

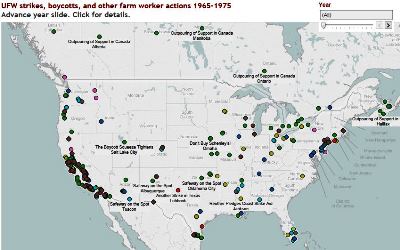

Click to encounter yr-by-year interactive maps of UFW strikes, boycotts and campaigns 1965-1975

The birth of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) in California in 1965 was a critical spark and integral office of the Chicano movement. The UFW was not merely a matrimony but what Cesar Chavez chosen "El Movimiento," a crusade with broad goals and broad back up. And although Chavez did not support Chicano cultural nationalism or consider himself a Chicano leader, the UFW inspired Chicano youth, radical activists, and civil rights organizations. The UFW appealed to many Chicanos because of its Mexicanness as highlighted in Chavez'due south Plan de Delano that spoke of the sacrifices the "Mexican race" had fabricated to seek breadstuff and justice.

The UFW began and pretty much remained a California-based organisation. The wedlock opened offices and conducted strikes in a few other states (notably Arizona, Texas, and Washington) merely was cautious about over extending itself. Yet the UFW's accomplish went far across its formal structures. In its heyday, the UFW seemed to belong to Mexican Americans everywhere who embraced "La Causa," the fight for justice in the fields and for justice everywhere. Moreover, the union's militancy set it autonomously from other Mexican American centre-class organizations while resonating with young Chicanos.

While UFW locals and strikes were largely confined to California, information technology'southward campaigns depended upon boycotts that were conducted on a national and international scale. The UFW's great grape boycott start in 1968 was successful and mobilized Chicanos and others throughout the country while generating worldwide attending. The cold-shoulder elevated the profile of the UFW and the Chicano movement more than any other outcome. The maps above show how boycotts and other support activities spread far beyond California.

La Alianza

The actions of La Alianza Federal del Pueblos Libres (La Alianza) as well influenced the early Chicano movement and its leaders. The Alianza was formed in 1963 in New Mexico and never expanded exterior of the state. The organisation wanted to repossess the land and water rights lost to New Mexican Hispanos but guaranteed past the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848. While initially La Alianza was an accomodationalist organisation, in 1967 when Reis Tijerina became its president, La Alianza was radicalized, embraced cultural nationalism, and rejected middle-class tactics for redress. Between 1967 and 1969, La Alianza occupied the Echo Amphitheater at Kit Carson National Park, raided the Tierra Amarillo Courthouse to make a citizen's arrest of the Rio Arriba County commune attorney, and attempted to reoccupy Kit Carson National Park, leading to Tijerina'sarrest and incarceration from 1969 to 1971. To younger Chicanos such as Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzalez of the Crusade for Justice and Jose Angel Gutierrez of the Mexican American Youth Organization, Tijerina who fiercely fought for land and justice became a model to emulate.

Crusade for Justice

The Crusade for Justice, founded in 1966 by Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzalez in Denver, Colorado, sought to showcase the virtues of the Mexican American community through theater productions, dances, and fiestas to create unity and generate a political dialogue of how "la communidad" could solve their ain problems. Early on on Gonzalez preferred to proceed the system local rather than transform the Cause for Justice into a statewide or national organisation.

The Crusade for Justice, peculiarly Gonzalez, provided the move with a powerful political ideology of Chicanismo. Gonzalez popularized the term Chicano, proclaiming an identity that rejected assimilationist goals and an culling to the characterization "Mexican American." Gonzalez denounced a history of cultural genocide at the hands of Anglo-Americans and urged Chicanos to fight back, an calendar described in his famous poem I Am Joaquin/Yo Soy Joaquin.

In 1969, the Crusade for Justice organized the Beginning Annual Chicano Youth Liberation Conference where "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan" was drafted urging Chicanos to adhere to the manifesto'southward cultural nationalism and the notion of Aztlan every bit both a real and symbolic homeland. The conference was attended by thousands of students across the Southwest who returned to their communities to build the Chicano student/youth movement. The event also fueled Chicanismo and the conference became an important turning point of when the term Chicano took root in the colloquial of the Chicano movement.

In 1970, the Crusade for Justice spearheaded the organizing efforts of the Raza Unida Political party in Colorado and the Midwest but its headquarters remained in Denver. At the same time, the organisation came under siege by law enforcement agencies and Gonzalez's power struggle with Jose Angel Gutierrez led to the Cause for Justice'southward political ascendancy to fade past 1974.

Raza Unida Party

Click to see twelvemonth-by-year interactive maps of Raza Unida Party

Like the Crusade for Justice, the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) was cultural nationalist and militant merely focused on education and political empowerment. In 1967, Jose Angel Gutierrez and five other undergraduates and graduates in San Antonio, Texas, established MAYO. The arrangement expanded only within Texas. MAYO initiated an estimated thirty-ix loftier school walkouts from 1968 to 1969 including the Edcouch-Elsa, Kingsville, and Crystal City protests that garnered media attending. In the political loonshit, MAYO organized what became known equally the "Chicano takeover" of Crystal City's school board and city council in 1970. This historic event established the Raza Unida Party in Texas and by 1972, MAYO was absorbed by the new party.

Formed in 1970, the Raza Unida Party (RUP) sought to achieve electoral political ability by creating an alternative to the nation'due south 2-party system, which according to Chicanos had been unresponsive, unrepresentative, and indifferent to the needs of people of Mexican descent.

RUP'south initial efforts were in Crystal City, Texas. Jose Affections Gutierrez and key supporters were able to elect party candidates to both the school board and the city quango. These victories proved that a third party could be a viable option to achieve balloter influence, and led to the expansion of RUP in Colorado, Arizona, New United mexican states, and California. Merely RUP'southward electoral accomplishments exterior of Texas were few with the exception of California where the party achieved some success in local elections. In California, our maps show that an estimated 93 new chapters were established from 1971 to 1973 . Withal, only in Texas was RUP listed as an official party and in 1972, the political party campaigned for the election of Ramsey Muniz for Texas governor. The Raza Unida candidate received nearly 220,000 votes, not plenty to win, merely an impressive showing.

Only the party's days were numbered. Beginning in 1973, support for RUP faded. And by 1974, only Texas continued to commencement new capacity which was an indication of its inevitable decline. Outside of Texas activities declined precipitously. Power struggles betwixt Jose Angel Gutierrez and Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzalez hurt the movement. Additionally, party members fought over ideological issues, dividing between those who had Marxist-Leninist and cultural nationalist orientations.

Brown Berets

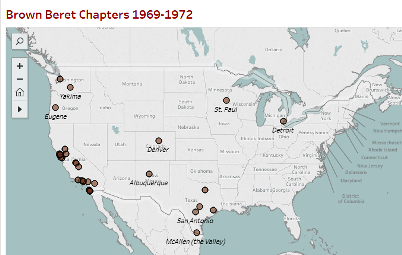

Click to see year-by-yr interactive maps of Brown Beret units 1969-1972

The Brown Berets were founded in the barrios of Los Angeles in 1967 and modeled after the Black Panther Party. By 1969, 29 capacity were established mostly in California but units were also established in Albuquerque, Denver, Detroit, San Antonio, St. Paul, and Seattle. They wore paramilitary attire and certain chapters trained in guerrilla warfare and use of weapons. One of their primary goals was to protect the Chicano community against law brutality. Brown Beret chapters also demanded equality in employment, housing, and education, advocated for bilingual education, pressed for voting rights, and the right to bear and utilise arms against racially motivated attacks. The Brownish Berets were involved in marches, anti-war protests, student-walkouts, and gained significant media attention when they staged an invasion of the Catalina Islands near Los Angeles in August 1972. Some other important directly action was their mobilization of the Eastward Los Angeles blowouts in 1968 where they acted every bit the security force for the thousands of protesting youth.

The Brown Berets high visibility and paramilitary opinion fabricated them a key target for infiltration, attacks, and harassment by local police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. When the Brownish Berets were disbanded by Prime number Government minister David Sanchez in 1972, a total of 36 chapters had been established primarily near college and university campuses.

MEChA

Click to see yr-past-year interactive maps of MEChA chapters 1969-2012

Before long after the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference, MEChA was formed with the intent to further Chicanismo and committed to the ideas of "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan." The manifesto provided a strategy to institute Chicano Studies Departments inside colleges and universities. To achieve this aim, "El Program Espiritual de Aztlan" called for the unification of all educatee organizations into one umbrella organisation, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlan which would become known past the acronym MEChA.

Most social movement organizations final just a few years and that is especially truthful for student-run organizations. But MEChA has been active on some campuses for nearly fifty years and the organization continues to grow, with more than than 500 capacity as of 2012.

In 1969, MEChA was founded in Santa Barbara, California where Chicanos adopted "El Programme de Santa Barbara." The manifesto provided a strategy to found Chicano Studies Departments within colleges and universities. By consolidating student's political power, MEChA became a significant on-campus political forcefulness and the proper noun signified a position to challenge social injustices and to reject assimilation through radical activism on-campus and in the community.

While the educatee-led arrangement formed in California, MEChA became a national organization with chapters in junior middle schools, high schools, customs colleges, and universities. All the same MEChA'due south geographic expansion was rather uneven. From 1969 to 1971, MEChA grew quickly in California with major centers of activism on campuses in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Diego, and the Riverside-San Bernardino area. Other early chapters were besides established in Washington, Oregon, Arizona, Colorado, and Indiana. In these years, new chapters were founded at universities and colleges exclusively.

Past the early on 1970s, a few MEChA chapters were founded in the East but mainly at Ivy League schools such as Harvard, Yale, and Brown University. MEChA largely remained a Due west coast organization. Expanding further in the 1980s, MEChA chapters began to appear in community colleges and high schools, but once more predominantly in California and specially Southern California.

Surprisingly, the arrangement did not catch on in Texas. A Mexican American Student Organization (MASO) was active at the University of Texas from 1967 until at least 1972 and students at St. Mary's College in San Antonio joined MAYO just there are no signs of MEChA chapters or other educatee groups in Texas until the mid-1980s.

As for Florida and other southern states, we have found no information well-nigh whatever chapters in this part of the land despite the growing Mexican American presence on campuses and in the region'south cities. Only if MEChA'due south geography was limited, its ability to survive and aggrandize in California and other western states was remarkable. Pupil organizations rarely last very long. But MEChA has expanded decade past decade.

During the 1990s, MEChA experienced a decade of slow growth nevertheless in the 2000s the arrangement saw an incredible upsurge of new chapters. High schools students led the charge predominantly inside California and likely attributed to the anti-immigration (H.R. 4437) legislation proposed in the mid-2000s. Robert Tijerina Cantu in MEChA Leadership Manual: History, Philosophy & Organizational Strategy (2007) includes an impressive directory of over 100 high school MEChA chapters that we have mapped as part of the project. Much like when MEChA was established, student mobilization has propelled and maintained the organization relevant for nearly fifty years.

Chicano Press

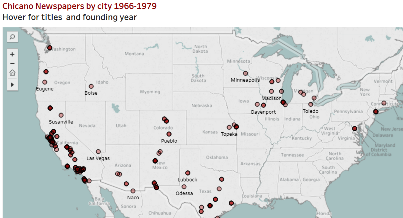

Click to run into year-by-yr interactive maps locating more than 300 newspapers and periodicals linked to the Chicano Motion 1969-1979

For those within and outside academic institutions, the Chicano press served as a medium to learn Chicano history, literature, and be informed of current news. Our database has mapped over 300 Castilian language newspapers and periodicals based in both small and big communities. Chicanos at many college campuses also created their own educatee newspapers. Withal, a significant number of these newspapers ceased publication within a yr or two, or merged with other larger publications.

Marc S. Rodriguez in Rethinking the Chicano Movement (2015) provides a multifaceted study of the Chicano movement and demonstrates how newspapers were a crucial medium for the move. The newspapers linked the cadre and periphery to create a national Chicano community. A pregnant component to the development of this national ethos was the Chicano Press Association.

Established in 1969, the Chicano Press Association tried to foster the growth these new media, arguing that the liberation of Chicano and other people required an agile press. Influential beyond its official membership, the CPA represented virtually twenty newspapers, mostly in California but also in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Florida.

There was nothing uniform about newspapers, magazines, and journals published during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some were published by organizations such as the UFW'south El Malcriado and the Brown Beret's La Causa and Regeneration, others by academy pupil groups like MEChA, nonetheless others by independent publishers who created newspapers for particular communities like El Grito del Norte from Denver and Caracol from San Antonio. Collectively the more 300 periodicals became the primary communication apparatus to broadcast ideas, information, and to expand the reach of the Chicano movement.

Further reading:

- Alaniz, Yolanda, and Cornish, Megan. Viva La Raza : A History of Chicano Identity and Resistance. 1st ed. Seattle, WA: Red Letter Printing, 2008.

- García, Ignacio. Chicanismo: The Forging of a Militant Ethos among Mexican Americans. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997.

- Gómez-Quiñones, Juan, and Vásquez, Irene. Making Aztlán : Ideology and Culture of the Chicana and Chicano Movement, 1966-1977. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2014.

- Muñoz, Carlos. Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Move. Rev. and Expanded ed. London; New York: Verso, 2007.

- Navarro, Armando. Mexicano Political Experience in Occupied Aztlan: Struggles and Change. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2005.

- Rodriguez, Marc S. Rethinking the Chicano Movement. American Social and Political Movements of the Twentieth Century. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Source: https://depts.washington.edu/moves/Chicano_geography.shtml

Post a Comment for "What Was the Focus of Protests by the Art Workersã¢â⢠Coalition in 1969?"